What Made the Eastern Australian January Storm Outbreak So Severe?

- Weatherwatch

- Jan 16

- 5 min read

January 16, 2025

The cleanup begins after one of the most significant January severe thunderstorm outbreaks in years finally comes to an end. However, for residents along the NSW coastline, a different threat is emerging with the development of a coastal low.

Photo courtesy of Gerkies Storm Chasing

Why Were This Week’s Severe Storms So Intense?

Severe thunderstorms in January across eastern Australia are by no means rare. Thunderstorms are fueled by warm, humid air—something often abundant in January. Even without some of the usual ingredients for severe storms, such as cold air and strong wind shear in the upper atmosphere, high instability alone can still generate storms, albeit more isolated ones.

The past two days, however, were quite different as mentioned in our previous article. A summer-like surface pattern combined with spring-like dynamics in the upper atmosphere created the perfect mix of instability, wind shear, and vorticity to fuel widespread destructive storms.

What Caused the Severe Thunderstorm Outbreak?

Slightly Negative SAM (Southern Annular Mode): The Southern Annular Mode is a curious beast - the same phase can cause wet or dry weather depending on the location, time of year and overriding climatic phases. The slightly negative dip in the SAM resulted in a stronger westerly influence across parts of Australia. This resulted in a broad trough establishing itself across eastern Australia. Negative SAM phases also can coincide with an increase in upper trough activity - that is, colder air in the upper atmosphere which is exactly what happened across eastern Australia.

Slightly negative SAM phase for much of January so far. Source: NOAA

La Niña Modoki: The term "Modoki" means "similar but different" - essentially, the Pacific Ocean is in a pattern that's similar to a La Nina, but different to a classic La Nina. Nonetheless, the impacts are also similar - that is a propensity for easterly winds to occur. The combination of a negative SAM and a La Nina in summer months often induces stormy conditions for a period because the westerly winds help push the heat from central Australia eastwards where it collides with the Pacific Ocean airmass. (Conversely, the same phase in an El Nino would likely drive hot, dry heat-wave conditions over the region).

It's not a classic La Nina, but there are La Nina-like elements to the Pacific Ocean. The two climate drivers clashed across eastern Australia. Source: NOAA

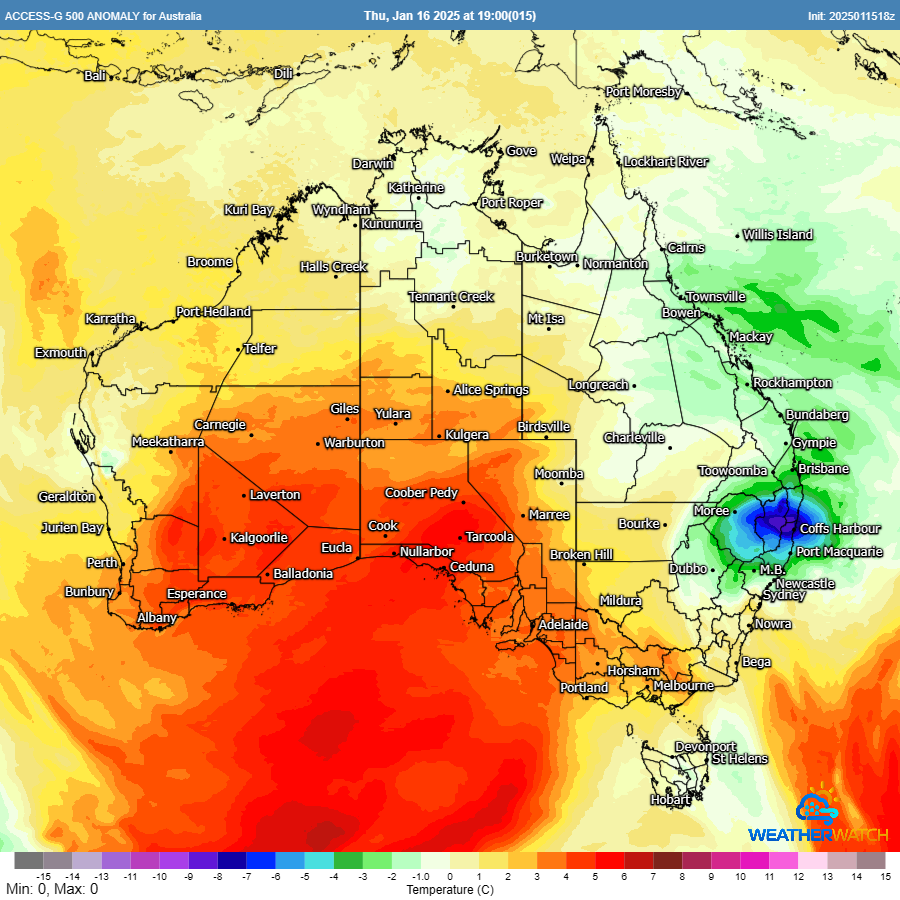

Cut-Off Upper Low: A strong upper low brought upper-atmosphere temperatures more than 8°C below average, resulting in extremely high instability and strong wind shear. This combination drove the formation of supercells and giant hailstorms.

Very cold air (more than 8C below average) was present across northeastern NSW helping to drive massive thunderstorm activity. Source: MetCentre

The Role of Chaos in Thursday’s Severe Weather

While Wednesday was an obvious severe storm day, Thursday's setup was far more complex, with a higher chance that things could have gone "wrong," resulting in little to no storm activity. The complexity stemmed from the strong upper-level dynamics, which often generate powerful surface winds. As a low-pressure system developed off the northeastern New South Wales (NSW) coastline, westerly winds began extending to the north of the system.

On a "typical" storm day, it’s often a race against time for storms to develop before the atmosphere dries out. However, early on Thursday morning, a large cluster of storms developed off the northeast NSW coast, pushing an outflow boundary westward. This boundary increased easterly winds and brought more humidity into northeastern NSW.

Although storm outflow can sometimes be too cold for further activity (e.g., Grafton barely reached 27°C before being hit by giant hail), the upper atmosphere was so cold in this case—coupled with a strong upper cold pool—that storm activity was able to persist even in cooler conditions.

Strong instability was present (CAPE 2700j/kg), while the increase in westerly winds from the outflow boundary resulted in bulk shear exceeding 50 knots (more than ample for supercells). Source: MetCentre

The high levels of surface moisture also drove strong instability, while easterly winds (gusting at 40–50 km/h along the coastline) combined with strong westerly winds aloft to generate very high levels of bulk shear and wind turning.

The result? A monster supercell storm that tore through the heart of the NSW Northern Rivers region, bringing giant hailstones.

The same boundary extended northwestward, helping to generate further severe storm activity across the northern areas of the Northern Rivers and into the Gold Coast Hinterland. These storms also delivered giant hail. Once again, the unusually cold air in the upper atmosphere allowed storms to thrive in an environment that would typically not support severe activity.

A Bounded Weak Echo Region (BWER) identified on the Weatherwatch 3D radar - a strong severe storm indicator. Source: MetCentre

Why Was a Small Storm in Brisbane So Destructive?

A particularly small but violent storm struck the eastern suburbs of Brisbane, causing extensive tree damage. It might seem surprising that such significant damage resulted from an otherwise small storm. However, as previously discussed, time was running out as drier westerly winds swept through the region. By this point, the lower atmosphere was rapidly drying, with humidity levels plummeting. At 1 pm, Brisbane Airport recorded 31°C with 82% humidity. Just an hour later, the temperature had soared to 37°C, and humidity had dropped to 32%, as gusty westerly winds swept through, further drying the atmosphere.

Image from Higgins Storm Chasing showing a very high base and developing microburst over Brisbane from an otherwise small storm.

One of the most significant dangers in thunderstorms is the occurrence of microbursts. Microbursts are small but intense bursts of wind that form when rainfall (or hail) evaporates as it descends toward the ground. This evaporation causes the surrounding air to cool rapidly. As cool air is more stable, it plunges downward. Upon reaching the ground, it spreads out horizontally, creating concentrated bursts of damaging or destructive winds.

This is precisely what happened during the storm in eastern Brisbane today, explaining why such a small, unassuming storm was able to produce so much damage.

Before and after sounding ahead and behind the westerly airmass at Brisbane AP. Note that the bases were very high after the drier air moved through but the atmosphere was still unstable. This allowed for the storm to survive in an otherwise unconducive environment while the dry air fueled the microburst activity. Source: MetCentre

The storm that tracked through Brisbane was much smaller than the Grafton or Gold Coast storms. Source: MetCentre

What’s Next for Eastern Australia?

With summer only halfway through, there are still several months left of the severe weather season. The wet season peaks from January to March, bringing the highest chances for flooding and tropical cyclones.

Attention now shifts to Western Australia, where several tropical lows are forming. Tropical cyclone development is becoming increasingly likely in the coming days.

Ensure Your Business is Prepared

If your business needs reliable, actionable weather information, reach out to our team of meteorologists for a free review of your weather services. We’ll help you prepare with a tailored weather services review, ensuring you stay ahead of whatever Mother Nature has in store.

Weatherwatch – your trusted partner in weather intelligence.